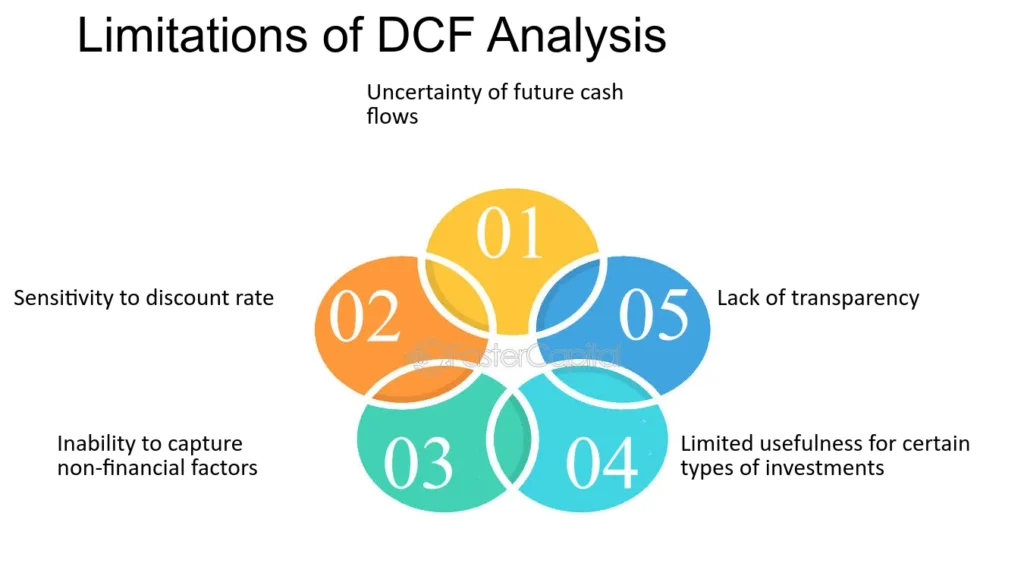

The discounted cash flow (DCF) method is a staple in valuation, but it comes with challenges. Understanding its limitations helps investors avoid over-reliance and makes room for a more comprehensive approach to assessing a company’s value.

Facing challenges with DCF valuation models? Let visitHomepage which connect you to specialists who can help you navigate the limitations.

Recognizing the Impact of Estimation Errors on Valuation Accuracy

In any DCF model, small estimation errors can have a big impact on the overall valuation. This is because the DCF calculation depends heavily on predicting future cash flows, discount rates, and terminal value. When these estimates are off, even slightly, they can lead to significant overvaluations or undervaluations.

For instance, overestimating future cash flows by just a few percentage points may make a business appear far more valuable than it truly is. Similarly, using an inaccurate discount rate, like underestimating the cost of capital, can make future earnings seem worth more than they should be. This can mislead investors into thinking a business is less risky or more profitable than it actually is.

A real-world example would be estimating the future earnings of a tech company based on past performance, without considering the industry’s rapid pace of change. Those optimistic projections might not account for potential downturns or disruptions. So, always ask: How realistic are the numbers used in the DCF? Consulting with financial experts or rechecking the underlying assumptions can help avoid these pitfalls.

The Risk of Over-Reliance on Subjective Growth Rate Assumptions

Growth rate assumptions are one of the most subjective aspects of a DCF model. This becomes risky when analysts rely too heavily on optimistic growth forecasts that may not materialize. Overestimating growth rates can inflate the value of a business, giving investors a false sense of security.

Take, for example, a startup in the renewable energy sector. If you assume the company will grow at 20% annually for the next decade, you might end up overvaluing the business. However, in reality, competition, regulatory changes, or market saturation could limit that growth. Underestimating these factors often leads to valuations that are out of touch with reality.

To mitigate this, it’s wise to use a range of growth scenarios—optimistic, moderate, and conservative. This gives a more balanced view and prepares investors for various outcomes. Ask yourself: Is this growth rate grounded in reality, or are there hidden risks that could slow it down? By staying cautious with assumptions, the valuation becomes more robust.

When DCF May Not Be the Best Valuation Method

While DCF is a powerful tool, it’s not always the best fit for every business or situation. DCF works best when future cash flows are predictable and stable. For companies with uncertain or highly volatile cash flows, using DCF can result in misleading valuations.

Startups, for example, often lack a consistent earnings history, making it difficult to forecast future cash flows accurately. Similarly, companies in sectors with rapid technological change or shifting consumer preferences may not be ideal candidates for DCF valuation. In these cases, alternative methods like Comparable Company Analysis (CCA) or Precedent Transactions may provide a more reliable assessment.

An example of DCF’s limitations would be evaluating a biotech firm in the early stages of drug development. Without consistent revenue, it’s hard to predict future earnings, making DCF an unreliable method in this scenario. So, consider: Is DCF giving the full picture, or is another approach better suited to this business? When in doubt, consulting a financial advisor can offer better insight.

Conclusion

While DCF is a valuable tool, its limitations mean investors must supplement it with other methods. A balanced approach to valuation helps mitigate risks and leads to a more accurate reflection of a company’s true worth.